Modernization

Learn more about government’s intention to modernize the museum to protect our historic holdings and provide better access to our collections.

The Triassic Period marks the beginning of the age of dinosaurs, and although we don’t yet know about any Triassic dinosaurs in British Columbia, we have a great record of marine reptiles from this time period in the province.

This summer I’ve had the exciting opportunity to examine a pair of ichthyosaur specimens housed here at the Royal BC Museum as part of an NSERC-funded summer research placement. One was collected in the 1990s from Holberg Inlet on northern Vancouver Island, and the other in 2020 along the shore of Williston Lake by a team of researchers from the University of Victoria.

Ichthyosaurs, meaning “fish-lizards” in ancient Greek, were generally large marine reptiles that resembled dolphins, but with a vertical tail fin which moved side to side rather than up and down like modern whales.

Research done by the Royal Ontario Museum and the Royal Tyrrell Museum collected large specimens from the northern interior of the province from the 1980s to the 2000s. Other specimens have been discovered on Haida Gwaii, Vancouver Island, and the far northwest of British Columbia. Both of the specimens at the Royal BC Museum were discovered in Triassic rock, but exhibit unique characteristics that differentiate and place them within the evolutionary history of the ichthyosaurs.

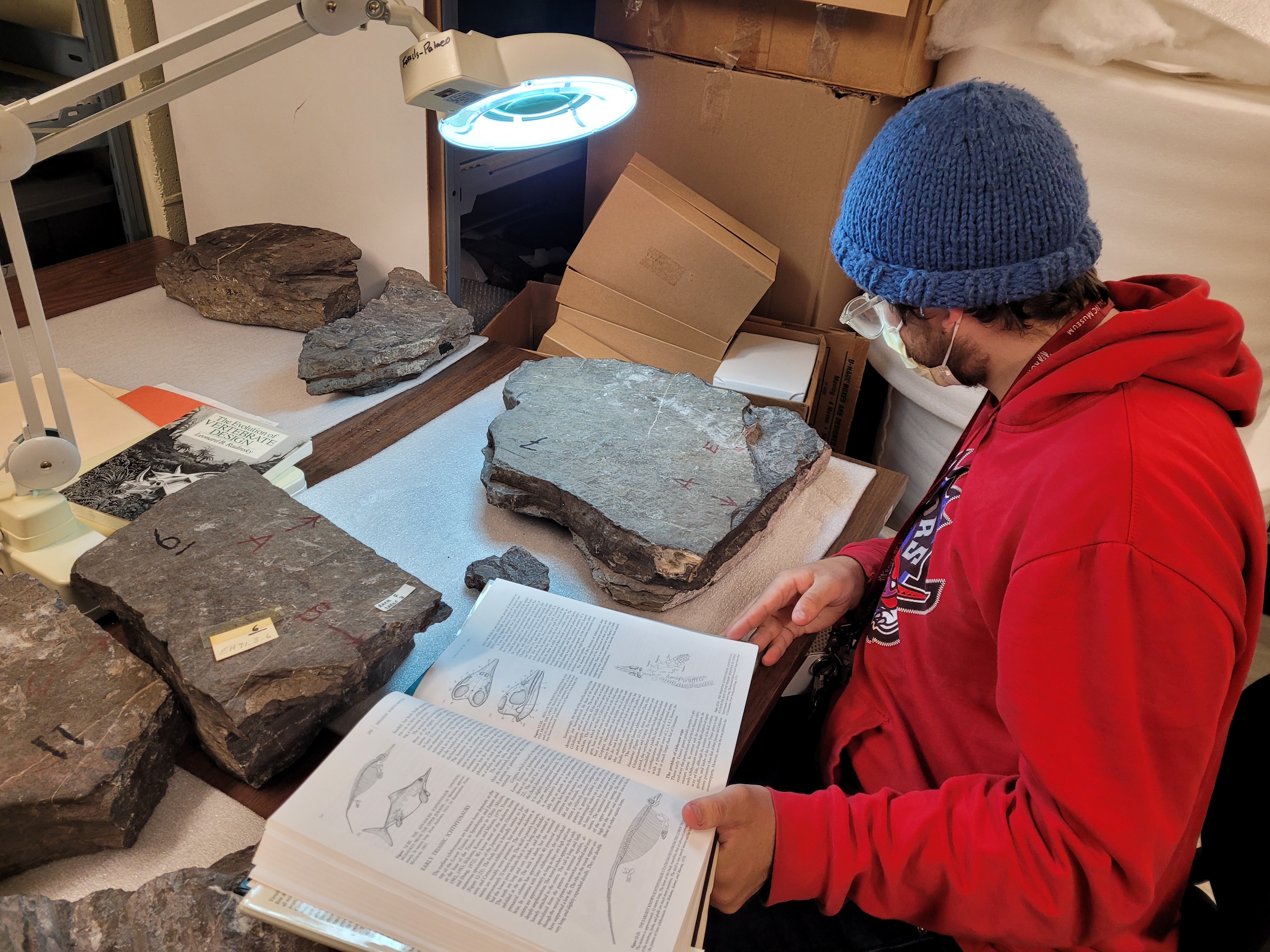

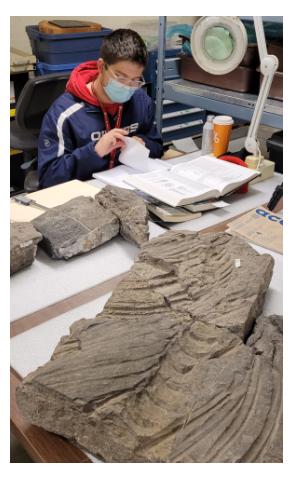

The main purpose of my research at the museum is to attempt to identify the skeletons, using photography and illustration, while learning more about the anatomy and evolution of ichthyosaurs.

The Holberg ichthyosaur is a large fragmentary specimen mostly consisting of impressions of a vertebral column and a series of rib impressions. It’s at least 3 metres long when the 20-30 stone blocks are laid out. This specimen has been hard to identify because it lacks a skull, but over the summer, I found that at least part of a flipper is present in the rock. The flipper is one of the more identifiable parts of an ichthyosaur skeleton, and the shape of the flipper bones suggests this specimen might be a shastasaurid ichthyosaur, which were among the largest vertebrates to ever live in the seas. The largest specimen, Shonisaurus sikanniensis discovered in northern British Columbia by the Tyrrell Museum in the 1990s, was 19.5 metres long!

The second specimen I’ve been studying is from Williston Lake and includes a sclerotic (eye) ring, most of a forelimb flipper, some fragmentary skull bones, and several teeth. I think this specimen might be a parvipelvian ichthyosaur, which were the only kinds of ichthyosaurs to survive the mass extinction at the end of the Triassic and live on into the Jurassic Period. The Williston Lake specimen was found in rocks from the very end of the Triassic, and is the first occurrence of an ichthyosaur of that age from BC. Ichthyosaurs of this age are generally rare globally, so this specimen may inform research into how ichthyosaurs changed through the mass extinction.

It has been a very special experience to work on these specimens at the museum over the summer and to contribute to the understanding of palaeontology in my home province. I hope I can continue to work on these fascinating creatures as I continue in my career, and that palaeontological research continues to be a focus at the museum.